Publisher: The British Journal of Photography

Characters of his works were Soviet ordinary people. They impressed the world with their open and weird idea of beauty and freedom. In early 90-ies his pictures were perceived as social. They were ruining the belief that post-Soviet Russia was asexual. Today the same pictures are recognized as X-ray of the characters’ interior life. The photographer Nikolay Bakharev is not tall, bearded and horn-rimmed, his hair red with grey. He residents in the East Siberian town Novokuznetsk of the Kemerovo Region and makes ordered shooting of the locals. He has been doing it over thirty years already. In summer he takes some side job, taking pictures in the beach. He was born in a Siberian village in 1946, he lost his parents when he was four, and he was raised in an orphanage till the adult age. Then he worked as a locksmith in the steelworks, until he took a camera in his arms. His pictures participated in dozens of international and Russian exhibitions. The Moscow gallery owners tried to move Bakharev to Moscow, but failed. His peculiar method hardly could survive in the capital, and the artist himself wasn’t pleased with the result. Finally, he returned home to Novokuznetsk.

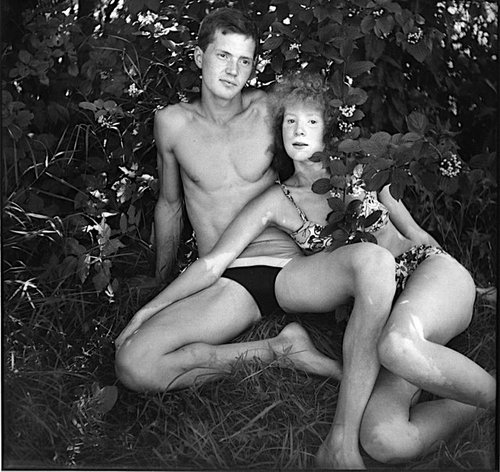

Since his first photographic sets shot in 70-ies (Having fun, Together, Couplets, Attitude) the main subject of Bakharev’s work were people in their intimate commonness, inhabitants of the Russian back country, al fresco or in private, among calendars with pictures, bottles of Soviet champagne, flowers and old glossy magazines, people in erotic positions.

Bakharev’s shooting involved exhausting hours-long modeling, which caused the models to abandon their traditional moral values in relation to nudity. One of Bakharev’s models, a student from Novokuznetsk, Julya, said, “Wishing to play a top-model changing dresses, you rush through your clothes, go and borrow pins and scarves from a friend, though, you know little that he (Bakharev) hardly cares for your modeling, borrowed from glossy covers, but he cares for your personal plastique, for your bodily interpretation of your internal image”. He creates a situation when the senile collective socialistic body is smashed into dozen of individual images, free of the Soviet hypocrisy. He observes and records this interpretation. “Denudation is not the aim, it is the technology, – Bakharev explains his strategy. – It is important to communicate with the environment and time”. His models sit for him among their post-Soviet living conditions, where provincial Kitsch of small-sized apartments expresses their aspiration for beauty. However, monstrosity of the Soviet texture is not the point. Photographic revelations of Bakharev don’t belong to the ethnographic plane. It is the ambiguous frankness of his characters that matters. Intimacy which didn’t exist in the Soviet social body and thus settled with various phantoms is the guide of this frankness. This are these phantoms that reveal themselves during many hours of modeling. Young and elder provincials get naked to remove not only their clothes, but their social roles, as well. They disgown their inwards. They show the audience their private phantom world of desire, their new roles in the real world, from which they are reliably protected with interiors of their homes. The interior where different people stay is comprehended as the common Soviet context, identical to the private context, as the private has no specifics and is identical to the common.

The models try to understand how the audience will see them. The story line of Bakharev’s pictures is that a person tries to realize him- or herself, his or her desires and embodiment before being seen by the others. (At the same time desires discovered during the meeting with the photographer hits the lack of experience in such case.) Bakharev’s works reveal the pains of freedom, tension attracts the audience. Despite the clichéd allurement is the center of these pictures, tension reveals that pleasure of modeling is artificial. It is seen that Bakharev’s models try to follow some stereotypes of modeling. Their positions are demonstratively frank, and they look straight into the camera. Classic images from reproductions, commercials and porn magazines are copied. It is some unusual amateur experience of making a body vendible and making it a product.

Bakharev’s characters show themselves through stereotypical images of pop-culture. The photographer shows us personal appropriations of his models without irony or cynicism, though, he is not indifferent, either. He always acts in favor of his models and actively cooperates with them. At once, he seems to know more of his models than they do themselves. Bakharev is looking for areas, where his true vision of his characters is revealed among stereotypes of mass culture and provincial ideas of interesting and good living. This true vision is the true breach, the verity of the private life, which speaks for itself in his pictures.

His pictures are distinguished by an inflexible role structure. The model always models, and the photographer follows his or her desires. This is a structure to attend the desire, where the desire is at first concealed. Differently speaking, making his pictures Bakharev acts like a psychoanalyst, though his client doesn’t speak about the desired, but shows it. Speaking used for analytical anatomization is replaced with body gesticulations.

We see triumphal manifestation of the common mankind in a simple Novokuznetsk life projection of some lorry driver or a hairdresser’s husband. The verity of Bakharev’s photographic view is the result of his characters not recognizing their own lives. His photography tells us the truth through sincere self-deceit of his models in front of the camera. It reminds us that our actions are always part of circumstances considered, and that our mistakes are always part of the truth.

The photographer shows how embodiment is involved into the self-context, which is different from context of human existence. He shows components of the image and dowers them with some individual sense. Bakharev inscribes a body into the system of natural or domestic shapes, makes lines of both visual and semantic eidolons. The visual eidolon as a homonym is when a body exchanges its visual meaning with the background. The semantic (synonymic) eidolon shows the body as a cultural denominator of a human and his or her environment (either nature or domestic interior).

Poetics of his pictures is within this system of eidolons.

Bakharev doesn’t just guess desires of his clients, but he also reveals cultural prototypes of their frank plastique. Taking their naively pretentious poses his characters unconsciously follow some old fashion. As a photographer finishing his work Bakharev makes the role chosen by his client convincing. Because of this his pictures may look like documents from different times. Together with his model Bakharev does something like cultural archeology, making provincial things authentic.

Protracting modeling and provocative communication during the shooting let his characters step over frames of public morals and concept of decency, making them almost ecstatic due to self-denudation. Oleg Nesterov shared his impression from modeling for Bakharev in Moscow with the Afisha Magazine. “He was shooting me through five long hours, and I was so physically exhausted that I almost had some feeling of flight inside me. Some energy spreads from him. His accurate, short and succinct phrases and gests create a kind of a merry-go-round near you. You don’t belong to yourself any longer, and you don’t try to play something anymore. This is how he gets your essence revealed… He is the greatest photographer of modern times”.